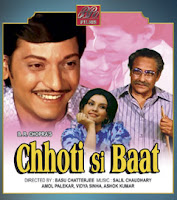

I’m always moaning about Hindi films that rip off Hollywood without successfully transferring the story to an Indian milieu. Well, here’s Chhoti Si Baat, a film that I didn’t even know was a remake of a 1960 British film (School for Scoundrels) because it has been transplanted so successfully to Bombay, circa 1975, and because Amol Palekar is so irresistibly adorable in the role of milquetoast Arun.

This charming main character is a hopeless, hapless office-going underdog so mild as to be nearly invisible. Nobody pays the slightest attention to him at work; by some miracle he has underlings, but they spend their days lounging communally around a transistor radio, blowing off Arun’s requests for reports and files blah blah blah and making him look bad with his own boss. He falls for a pretty girl, Prabha (Vidya Sinha), who works in another office, but he lacks the nerve to speak to her or even to get on the bus after her when the conductor tells him it’s full (which it doesn’t seem to be—maybe things were different in what the IMDb summary calls “pre-hypercongestion Bombay”). But he adores her, so he follows her around just to be near her and her gauzy polka-dot sarees.

|

| Vidya being dotty. |

It takes a while, but that’s not to say that nothing happens. Arun is Mitty-ish as well as Milquetoastian, so we get to see events play and replay in his imagination. It's fun to try to guess what's real and what's only Arun's dream--or nightmare. Here’s one of the film's insanely fabulous bits for those who adore self-referential Bollywood (me! me!)--the song “Jaaneman Jaaneman,” which purports to be a part of a film Arun is watching in a crowded movie theater:

Dharmendra plays the boy, wooing Hema Malini the girl, and Arun smiles happily at this natural onscreen pairing. But then in his imagination, Hema is replaced with Arun’s own dreamy girl—in the arms of the studly Dharmendra. See Arun squirm! But a moment later Arun has willed himself into the scene, having replaced Dharmendra, and audience-member Arun can relax again.

Outside the movie theater, Arun is equally plagued with jealousy. Prabha’s coworker, a smoothie with a scooter (Asrani, whom I will always think of as the jailer from Sholay), starts offering Prabha lifts to work, taking away Arun’s best chance to talk to her without looking like a creepy stalker. This interference provokes Arun finally to muster the courage to ask Prabha to lunch, and she accepts—but Asrani is there in the restaurant and invites himself to join them, ordering like a big shot before whisking Prabha back to the office and sticking Arun with the check.

After a few more misguided attempts to impress Prabha, each of which fails more spectactularly than the last, Arun seeks guidance from fortune tellers and bogus sadhus before heading to Khandala to find Col. Julius Nagendranath Wilfred Singh (Ashok Kumar), India’s biggest fixer. Why, he’s so famous that Amitabh Bachchan himself, in a squee-inducing cameo, pops in to ask for advice, confers with the colonel, touches his feet, and dashes out. (Is this an Arun fantasy, too?)

Arun naturally follows the Colonel’s advice--come on, wouldn’t you? In short order Arun turns himself into the kind of modern swell who can eat Chinese food with chopsticks, psych out his opponent in table tennis, and trounce Asrani at his own game. Prabha is his!! But has Arun, in the process of becoming a man who can play Dharmendra, lost himself? Will he remain worthy of the “character certificate" he has offered to show the girl he loves? Will he turn Prabha into the kind of girl who wouldn't be caught dead in a dotty saree?

By raising such questions, it’s clear that the film wants Prabha and Arun to end up together on very old-fashioned terms. It’s not enough for Arun to reveal that he loves Prabha and show some backbone. He has to prove that he is able to become that obnoxious westernized striver so that he can firmly reject that path and succeed in remaining a sweet and decent boy, albeit one who finally knows how to command a little respect from a bored office peon.

So Arun drops his invisibility--giving everyone else the chance to see the basic decency that Prabha has identified all along. And Asrani? He traipses off to Khandala to meet Col. Julius Nagendranath Wilfrid Singh and see if he, too, can find his way back from westernized striving to the sweet and decent path, which is after all where one finds girls like Prabha....